Work in the Leaves: The Real Cost of Tea and the Romance We Don’t See

- Lorela Lohan

- Aug 9, 2025

- 10 min read

Part II of a 4-part series:

Following the Leaf — A Journey with Jeff Fuchs

In this interview of 4 parts, Jeff shares insights on tea culture, from its romantic myths to its gritty realities, and reflects on a life shaped by tea and travel.

Part II - Work in the Leaves: The Real Cost of Tea and the Romance We Don’t See

Focus: Labour, economics, sourcing, grit

Challenges of Sourcing Tea and Honouring Its Origins

Lorela: Tea has fueled your many expeditions, but it’s also a business for you. What have been the most underestimated challenges you faced as a tea entrepreneur and explorer, especially when sourcing from remote or politically sensitive areas (like Tibet)? Any lessons learned on working directly with far-flung producers?

Jeff:

One significant challenge – and something often under-appreciated in the tea world – is recognising the deep expertise of local farmers and producers. I think we in the West sometimes underestimate the knowledge of those who grow and live with tea. These individuals may not use our complex terminology, but their understanding of tea is instinctive and well-honed.

For example, a farmer in Yunnan who has tended ancient tea trees for decades can tell you in one simple sentence more truth about those leaves than any glossy marketing pamphlet. Their fingertips, eyes, and nose know the tea. I’ve sat with farmers who describe the character of the tea from the north slope of a hill versus the south slope in such a straightforward, matter-of-fact way – yet those observations cut through all the marketing gimmicks and myths.

I often found myself thinking:

If only we could bring some of these tea growers to international tea festivals! They would steal the show with their unvarnished wisdom.

So, one challenge has been bridging that gap – respecting and conveying the farmers’ perspective, which is sometimes at odds with the narratives that the modern tea market has built.

When I co-founded a small tea company back around 2008, we decided to do things very differently. We focused exclusively on sheng pu’er (raw pu’er) at a time when almost everyone in the West was chasing shou pu’er (the dark, fermented “ripe” pu’er). It was a bit radical – sheng pu’er was not well known or popular outside of Asia then. But having lived in Yunnan, I knew that locally this raw pu’er was cherished; it’s what the villagers drank daily. We felt it was important to highlight what the locals valued. Each month, we’d send subscribers a different sheng pu’er tea, and crucially, we’d include the story behind it: where it was grown, who made it, and how they describe it.

Our role was almost like messengers. I interviewed farmers (in Mandarin, since many didn’t speak English) to gather their descriptions. For instance, a grower might tell me, “Tea from this north-facing slope has a cooler, gentler character than from that south-facing slope,” or they might use a local nickname for the tea. We’d pass these nuggets straight to our customers. Instead of us inventing flowery language or over-romanticising, we let the producers’ voice come through.

This was challenging at times – it meant translating not just language but culture.

Many nuanced terms in Mandarin, in local Yunnan dialects, in Thai, in Japanese, Korean, etc., don’t have direct equivalents in English. We had to convey concepts without losing their meaning. But I think doing this was worth it. It built trust and authenticity. Our subscribers loved that each tea came with a window into a remote village and the people behind the leaf. Back in 2008, that level of traceability and storytelling was not common. Now it’s more accessible, but at the time, it felt like an uphill battle convincing people to care about a single-origin story. We learned that tea drinkers appreciate real information. By sharing the origin stories, we credited the consumers with the ability to understand and enjoy tea on a deeper level.

Another challenge is maintaining integrity while scaling up.

Tea is a business, and there’s always pressure to cut costs or simplify the story to move products. But scaling often comes at the expense of the source. Even today, many small farmers are getting paid roughly what they earned 8–10 years ago, despite rising costs of living. The middlemen and retail end see bigger margins, but the people at origin often do not. That’s not sustainable or ethical.

To me, part of being a tea entrepreneur-explorer is to continually advocate for the value of the source.

The farmers’ craft, their environment – these are what make tea truly great. Interestingly, we’re seeing the market slowly wake up to what I call “the old ways”. Tea that is grown in a biodiverse, pesticide-free environment – as it traditionally was for centuries – is now prized and fetches crazy prices among connoisseurs. In Yunnan, for example, wild or ancient arbour teas grown in mixed forests (not monoculture plantations) are sold for astonishing sums.

People slap terms like “biodynamic” or “permaculture” on it, which are essentially new words for how things were always done in those remote tea mountains. It’s a bit ironic – and perhaps problematic – that we rename these traditional practices to market them. But at least there’s some recognition coming full circle: acknowledging that an untouched forest garden produces incredible tea.

All this has taught me that tea quality and tea culture suffer when we lose sight of origins. If we chase short-term profit by over-harvesting, heavy pesticide use, or selling a story that’s too disconnected from reality, we eventually kill the very thing that makes tea special. There are parallels in places like Darjeeling or other regions where intensive farming led to soil fatigue and declining quality.

As an explorer-turned-entrepreneur, my mission has been to not lose that balance – to honour the romance of tea and the reality of those who make it.

It’s not always easy, but it’s the only way to ensure tea has a vibrant future.

Connecting with Source: Travel, Sustainability, and Community Insights

Lorela: You’ve lived and travelled in so many tea regions – Yunnan, the Himalayas, Taiwan, etc. How have these experiences shaped your understanding of tea communities and sustainability? What insights have you gained about keeping tea culture (and farming) sustainable for the future?

Jeff :

The biggest insight from my travels is the absolute importance of connecting with the source.

If you’re serious about tea – whether as a seller, educator, or even an enthusiast – there is no substitute for going to the tea lands and spending time there. I wish it were a job requirement in the tea industry that everyone had to visit a tea origin at least once! It changes your perspective fundamentally.

For instance, during the 11 years I was based in Yunnan, China, I’d regularly head down to the tea mountains of Xishuangbanna – places like Bulang Shan, Yiwu, Jingmai, all these famed pu’er tea villages. One beautiful custom there is that when you visit a farmer or a producer, the first day (or two) is just about hospitality. You’ll sit, eat interminable meals, drink lots of tea, chat about family and life, and not a word of business is spoken initially. This isn’t some calculated tactic; it’s just their way of life. Relationships and trust come first. Only after that foundation is laid (or reaffirmed, if you’ve been there before) do you even broach the topic of buying tea or evaluating the harvest. I found that so grounding. It taught me that tea was never just a commodity for them – it’s part of their community fabric.

The sustainability of tea, in their eyes, starts with sustaining human relationships.

Yunnan, in particular, has a wonderfully unhurried culture. I often joke it’s the most content, slow-paced province in China. People there can have a tea session that lasts four hours, punctuated by smoking tobacco, maybe sipping some locally distilled alcohol, then more tea – all in the same sitting! I remember walking into little tea shops in Menghai or Jinghong: the air would be thick with cigarette smoke, folks would be laughing, shouting, pouring tea in these tiny cups, sampling one cake after another, and simultaneously maybe striking business deals or gossiping about neighbours. It was chaos compared to the serene tea meditations I was used to – but it was fantastic.

Those tea houses functioned as community hubs.

They didn’t stop life to appreciate tea; they wove tea into the fabric of life. That showed me a kind of organic sustainability of tea culture – tea as a normal, accessible part of everyday socialising, not something elite or precious.

From a farming and trade standpoint, my travels also highlighted some harsh realities. For one, as demand for fine tea has exploded, not everyone is sharing in the benefits. The price of a top-tier pu’er cake might be sky-high in Guangzhou or on the international market, but the family who grew and processed that tea might still be living very modestly. In remote areas, I saw that many farmers didn’t have much bargaining power, especially if they sold to middlemen. Some told me, “We’re still getting what we got years ago per kilo, even though the end price has tripled.”

Inflation and the cost of living have risen, but their income hasn’t kept pace. That’s not sustainable for them long-term – if farming doesn’t pay, the next generation will abandon it.

So, one insight (and call to action) is that we need to ensure the value trickles down.

I encourage anyone sourcing tea to pay a fair price and to be transparent about it. In the West, consumers are increasingly interested in ethical sourcing – they ask, “Are the workers paid well? Are the farming practices sustainable for the land?” These are great questions. As someone who has seen both ends, I try to advocate for the farmers’ worth. They are the stewards of the land and the artisans of the leaf. If they can’t make a living, we all lose.

Another key aspect of sustainability is ecological. In my journeys, I observed that the healthiest tea ecosystems were the traditional ones – mixed forests, old-growth tea trees coexisting with other plants and insects. In places where tea was grown like a factory crop (monoculture, heavy agrochemicals), you’d sense an imbalance – soil erosion, pests requiring more spraying, etc. Thankfully, many of the remote areas, like those old pu’er tea mountains, had maintained more organic practices simply because that’s how it was always done. Now there’s a movement to recognise and preserve those methods. When I hear terms like “regenerative agriculture” or “permaculture” being applied to tea, I smile because the mountain folks have been doing that all along – planting tea under shade trees, letting chickens roam to eat bugs, using natural compost.

So part of sustainability is learning from these traditional models and perhaps giving them due credit (and maybe a premium price) in the marketplace.

Travelling also made it obvious that tea knowledge flows both ways. I learned at least as much from sitting and listening to a farmer or an elder in a village as they might have learned from me about foreign markets. One thing I’ve tried to do is act as a conduit: take the wisdom from the fields and share it with consumers, and take consumers’ appreciation or questions and share them back with the farmers. It might be as simple as telling a farmer, “People abroad loved your tea, they found it had notes of honey,” etc., which delights them to hear. Or telling consumers,

“This tea maker says he always brews in spring water because the minerals round out the flavour,” which might encourage a tea lover to think about their water. It creates a loop of learning.

Nowadays, I’m heartened to see more tea enthusiasts making pilgrimages to the origin. Even young people with just a budding interest are strapping a gaiwan and a few cups in their backpack and heading to Yunnan or Uji or Darjeeling or wherever. They save up, they go meet these farmers face to face, they share tea across languages – it’s beautiful. It’s also educational in a way no book or website can replicate.

I’ve met so many travellers in remote tea areas who say the experience was life-changing. They not only tasted the freshest teas but also witnessed the hard work and the love that goes into them. That creates a lifelong respect for tea.

That ties into another insight: sometimes the best way to appreciate tea’s nuances is to strip away the marketing and just taste it in context. I’ve been pouring teas without being told what they were – only to be floored and then later learn it was something like a wild purple-leaf pu’er from a village I’d never heard of. Those kinds of experiences stick with you and, ironically, make you more eager to learn. On the flip side, I’ve seen over-marketing do damage – a seller gives a guest a long preamble about “this tea has hints of orchid and chestnut and was picked by monkeys on a full moon,” and by the time the person sips it, they’re so busy searching for those notes that they forget to just enjoy the tea!

My travels taught me that letting the tea speak for itself can be the most powerful education.

Finally, from a community standpoint, I observed that in many tea-growing regions, tea is not viewed as an exclusive luxury; it’s a daily staple and a social glue. In Yunnan, everyone in the village might gather for evening tea drinking; in Tibet, any guest, even a stranger, is immediately given a bowl of butter tea – no questions asked. That generosity and openness are something I try to bring back with me. It’s made me more of an evangelist for accessible tea. Yes, I love a rare aged pu’er or a top-notch gyokuro, but I will equally relish a simple cup of Moroccan mint offered by a shopkeeper in the bazaar. It’s all part of the same continuum. If we lose that accessibility – if tea becomes too rarefied or expensive for the average person – then I think we’ve failed the legacy of tea.

So the takeaway from wandering the tea world is: stay connected to the source, champion the people behind the leaf, and keep tea rooted in the community. That’s how we ensure that both the culture and the crop of tea remain rich for generations to come.

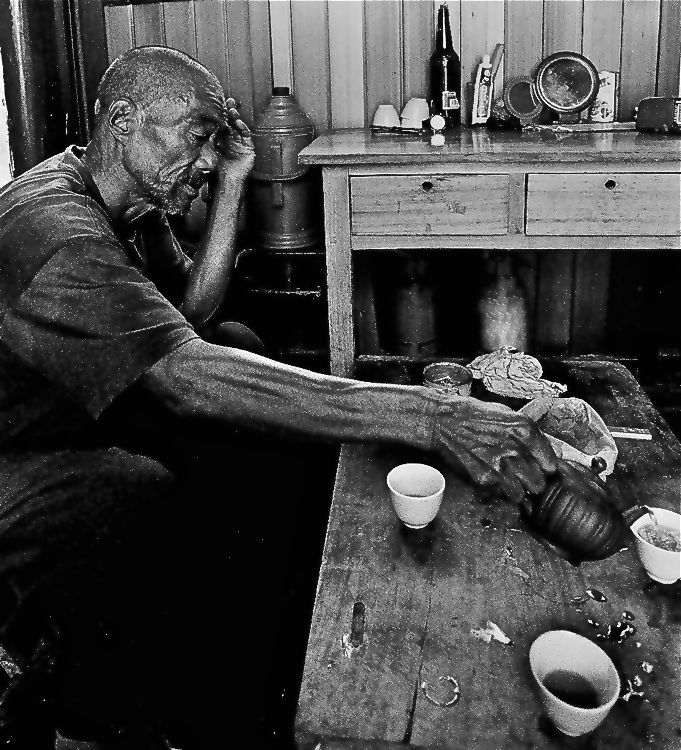

PHOTO CREDITS: Jeff Fuchs

Your point about the sourcing challenges for businesses looking to offer authentic Pu-erh is spot on. Consistency in the flavor profile from one batch to the next is absolutely critical for customer retention, but it's often the most difficult variable to control with artisanal products. This really underscores the importance of finding partners who specialize not just in quality tea, but in the logistics of B2B supply. For anyone navigating this, focusing the search on dedicated wholesale Pu Erh cake suppliers can be a game-changer for ensuring both quality and reliability.